Part two of an investigation into achieving balance in spirits-driven cocktails.

[Author’s Note: The following post was mostly written back in June to document the second half of my investigations in acidity in spirit-driven cocktails. July saw me at Tales of the Cocktail and then in early August I turned all of my energies to starting up the cocktail program and bar at Daniel Patterson’s restaurant Plum. Due to differences in style and vision, I parted ways with Daniel & Company few weeks after the opening of Plum Bar in mid-November. In the interest of getting back into blogging, I’ve decided to publish my work to date, though clearly there’s more work to be done. As I get some of the questions it has raised answered, I will report back.]

Back in March I wrote about trying to improve a spiritous cocktail I had created (Criollo #2) which on reconsideration, I felt turned too sweet. The concept started out as a kind of ‘Black Manhattan’ with amaro taking the place of vermouth but I discovered that as I added more amaro I was also increasing the amount of sugar. That in turn led me to think a lot about the options we have for bringing acidity to a cocktail. It’s acid which helps brighten and highlight all the other flavors. However, without citrus as an option, we’re at a distinct disadvantage. I focused on the properties of vermouth, which I described as a kind of super-ingredient, bringing not only needed acidity into a cocktail but also many other interesting and complex flavors. I decided at that point to “do some serious science” by which I meant to I wanted to measure the PH of common cocktail ingredients to determine exactly how acidic. or not, they were.

The Gear

The first order of business was to decide how best to make the measurements. Though my analytic chemist brother-in-law recommended using precision PH strips (different from plain PH paper on a roll) I opted in the end for a digital PH meter. These have become pretty inexpensive over the years, with several models less than $100. After some research, I opted to purchase an Oakton phTestr 10, which can be had for as low as $75. (I actually think many of the meters I looked at were just re-skinned versions of this or vice versa.) Key features of this model are:

- A double junction probe (generally considered longer lasting—the probes are filled with reference material that can dry out over time).

- Automatic temperature compensation.

- Support for three calibration points.

- Accuracy of PH 0.1.

I also checked with the manufacturer to determine if it was suitable for taking measurements in alcoholic solutions in excess of 50% (100-proof). It was! Finally, I purchased a set of reference buffer solutions, critical for calibration which must be done before every use. Should you buy a meter of your own, it’s important to note how many and which calibration points are supported. The buffer solutions you buy must match these calibration points. There are in fact two slightly different calibration systems: one called “US” based on the points 4.01, 7, and 10.01 and one called “NIST” based on the points 4.01, 6.86, 9.18). The Oakton meter supports both.

“There’s science to be done!”

To date I have tested over 65 cocktail ingredients, including aromatic bitters, syrups, and common citrus juices. The results are summarized in the table below. (NOTE: you can click on the image to download an easier to read version of the table in PDF.) As a reminder for non-science geeks, PH 7.0 is considered neutral, neither acidic nor basic. As PH goes down from 7.0, acidity increases; as PH goes up from 7.0, alkalinity (or basic nature) goes up. Tap water is generally about PH 7.0, though as it gets “harder” (includes more dissolved salt and minerals) the PH value increases. A lot of tap water is slightly basic.

You’ll notice that with only a single exception (discussed below) common cocktail ingredients range from neutral (e.g. gins and sugar syrups) to distinctly acidic (e.g. citrus juices). The most acidic ingredients are, unsurprisingly, lemon and lime juices which measure below PH 3.0. These then set the “gold standard” for bringing acid into a cocktail. A relatively small amount of these juices can be used balance against a large amount of sugar. All other ingredients are distributed between PH 7.0 (neutral) and PH 3.0 (moderately acidic). If we consider them by class, some interesting patterns emerge.

First are the vermouths, sherries, and madeiras: non-distilled products, all based on grapes. These all fall between PH 3.0 and 3.7 and are as a class the most acidic ingredients after lemon and lime juices. Carpano Antica Formula and Dolin rouge are the most acidic members with a PH of 4.0. As I had previously speculated, it’s the acidity in vermouths complemented by all the other flavors they provide that makes them such welcome additions to spirit driven cocktails, or really any cocktail in which we use them. (And I remain encouraged that my enthusiasm for cocktails using sherry and maderia is well founded.)

Second, distilled spirits which start life or are sold at high proof (i.e. are highly distilled) and which spend no time in wood are pretty much neutral. This covers gin, vodka, “white dog,” and products like Everclear. Any acidity that may have existed in the source material prior to distillation has been eliminated. Contrast these pisco, which is made from grapes, distilled only once, and spends no time in wood. PH for the two piscos I tested were 4.1 (Encanto) and 3.8 (Oro), distinctly more acidic than gin or GNS. Also consider the case of Ransom Old Tom gin, which has a PH of 4.3. The Ransom is allowed to rest in used pinot noir barrels, long enough to develop its distinctive color. It also apparently absorbs some acids left behind by the wine.

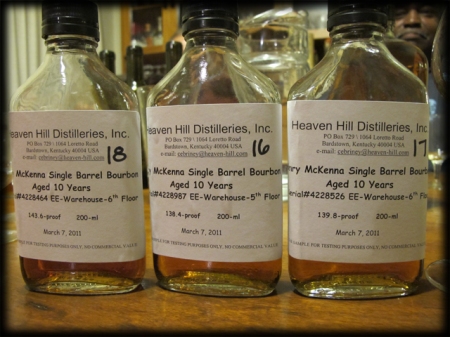

You’ll also see that spirits which are aged in wood appear to develop acidity over time. I am hesitant to draw too much of a conclusion about this phenomena since my data set is limited in this respect and there are so many variables when it comes to barrel aging: e.g. type of oak, amount of char, new vs. used, temperature/humidity during aging, previous contents of barrel, etc. Still, it is interesting to note that the most acidic distillates, the 23 year old Black Maple Hill rye and the 18 year old GlenDronach, are also the oldest spirits I had available for testing.

Another interesting ingredient to look at is the liqueur St. Germain. which is almost as acidic as some of the red vermouths. Compare that Cointreau, which is practically neutral. This explains, to me at least, why it’s been such a successful product, meriting the sobriquet “bartender’s ketchup.” While it brings lots of sugar, it’s also pretty well balanced in itself. Adding it, even in large amounts, to a cocktail isn’t likely to upset things very much.

One last observation: there was only one ingredient which measured distinctly basic (high PH). That was the Rothman & Winter creme de violette. This was so unexpected that I measured it twice on two different days just to be sure I hadn’t made a mistake. I am speculating this is caused by whatever has been used to color this product, which is a rather deep violet. I am hoping that the folks at Haus Alpenz will be able to answer this for me at some point (and I will certainly post an update if I learn anything).

There’s Always More to Do…

I will continue to test the PH of new ingredients and update my database. Let me know if you’d like a copy. I am also going to be talking to distillers, to see what they have to say about some of my observations, particularly regarding acidity derived from barrel aging. I’d like to understand what’s going on there better. Are significant acidic compounds present in the wood, which then dissolve in the distillate? Do barrels which have previously held wine or sherry cause distillates then stored in them to become more acidic than otherwise?